Interview with Dawn Roe

Interview with

Dawn Roe

March 2021 Digital Resident

My work explores lens-based practice as a mode of representation allowing for poetic and critical engagement with culturally charged sites of significance, as well as those presumed to be neutral. The resulting imagery is at once metaphoric and banal, emphasizing the arbitrary relevance of the distinct forms pictured. Combining a documentary approach with direct intervention, my process incorporates multiple reproductive methods including digital imaging, film, and video. Sensitive to the role of the camera in contributing to the proliferation of familiar, constructed images of landscape, I made a deliberate decision in recent years to incorporate (potentially) less mediated photographic processes including cyanotype prints and other UV-based contact exposure methods.

Working between and within the still and moving image, my projects examine the role of these media in shaping personal and social understandings of our environment through site-responsive engagement. Drawing on conventions of photography and cinema as emblematic of archived experience, the premise of evidentiary authenticity is deliberately probed via found and fabricated situations that are traced, replicated and transformed. Expansive presentation modes place sequential and composite imagery in relation as imperfectly contiguous screen-based and print forms, stressing the fragmentary nature of perceptual response. The ephemeral state implied by the time-based recording of physical elements is distinct from the printed reproduction – a stable frame that persists, suggesting all matter is sound enough to endure inevitable and relentless shifts, however benign or catastrophic. This approach purposefully unravels our collective understanding of the perceived world – and by extension, our struggle to orient ourselves within a shared global space that is rapidly transforming.

-Dawn Roe

Mineral House Media: What is your history as an artist? Where did you first find your passion or inspiration to create? What brought to you where you are now?

Dawn Roe: Hmm…such a tough one. I didn’t necessarily grow up thinking I wanted to be an artist, but was always just pretty curious about the world, generally - lots of looking and thinking, and questioning from a young age, I guess. From my late teenage years to mid-twenties I took a pretty meandering path that eventually led me away from my home state of Michigan to Portland, Oregon where I would live for 10 years in the 1990s and end up completing my undergraduate degree in art at a small college with a really strong BFA program just outside Portland called Marylhurst. I found my way to Marylhurst via the Northwest Film Center where I was initially studying experimental cinema. They had a cooperative program with Marylhust, which worked out great for me. The faculty in both of these programs had a profound impact on me and remain mentors and friends.

That decade in Portland was a transformative time for me, and certainly shaped my ideas around art and artmaking. My formal education was juxtaposed with the DIY culture embedded in my shared community of punk and indie musicians, writers, zine makers - artists of every variety really. There was fantastic energy and joy, but there was a flipside as well. Many of us struggled with mental health and substance abuse issues, and there was loss along the way. During my final year of undergraduate study, I made the decision to leave Portland and began applying to grad school. As I was already 30 years old at the time, going right into grad school made sense for me, as I was eager to work with a new group of faculty and fellow artists and just really needed to leave Portland. This decision turned out to be the right one, as my three years in the Studio Art MFA program at Illinois State University were equally pivotal, bringing me to a healthier mental and physical space. It was here my focus shifted from working with photography in a more traditional, documentary style to a more expansive mode that led me to begin staging works and considering working with the moving image again.

MHM: What sort of music do you like to listen to? Does it directly inform the vocal sound components of some of your work?

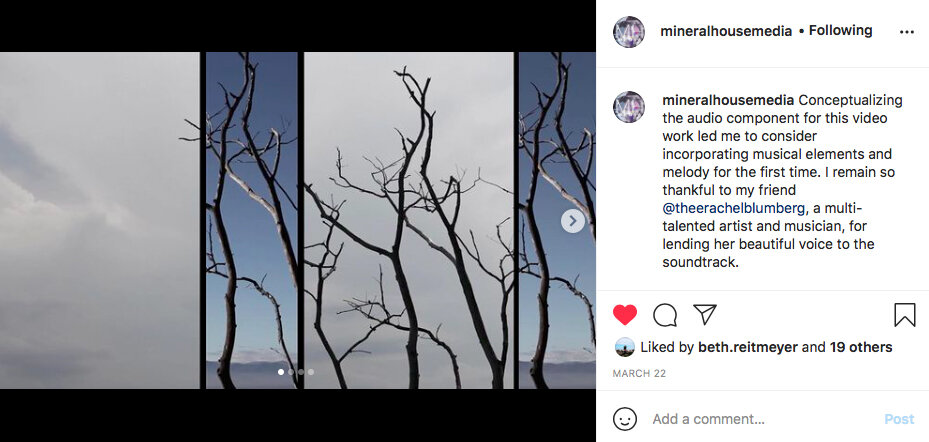

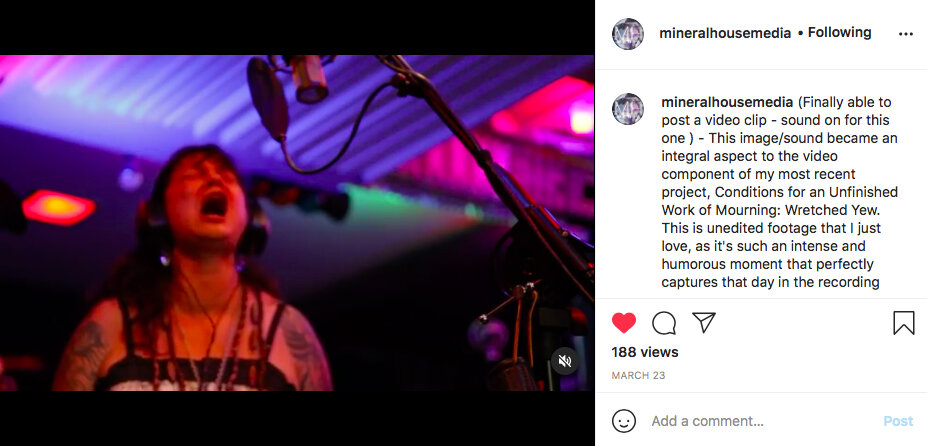

DR: Like most people, it’s a pretty wide variety, but I do tend to veer between extremes - from intensely bombastic and scream-y to more somber, melancholy and melodic sorts. I worked in a somewhat infamous club in Portland for years called Satyricon, known for hosting punk and garage acts as well as indie singer/songwriters. A lot of what I listen to would have been played there, either live or on the jukebox - too many bands/people to list, really. But I’ve always listened to a lot of old soul music as well. And yes, all these things directly inform the vocal components of my work for sure. Portland musician and artist Rachel Blumberg contributed her beautiful voice to one of my video works, The Sunshine Bores | The Daylights, and a group of Portland musician friends (Jerry (A.) Lang; Jillian Wieseneck; Dan Eccles; Jennifer Shepard; Dean Miles) produced the audio components to my most recent project, Wretched Yew. Jen Shepard’s vocal track is a hugely vital piece to that video, including a blood curdling scream that gives me chills in the very best way every time I hear it.

MHM: You talk about your work as being site specific, can you tell us more about the different spaces you have worked with? How do you choose a space? How are the spaces different or similar?

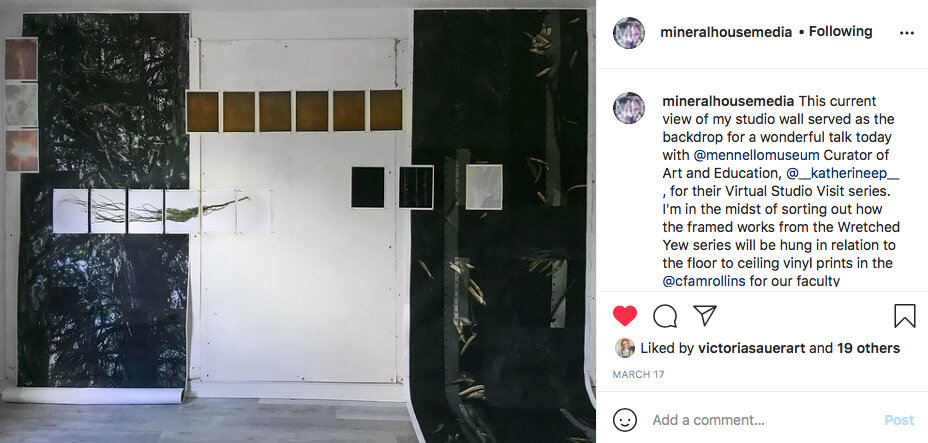

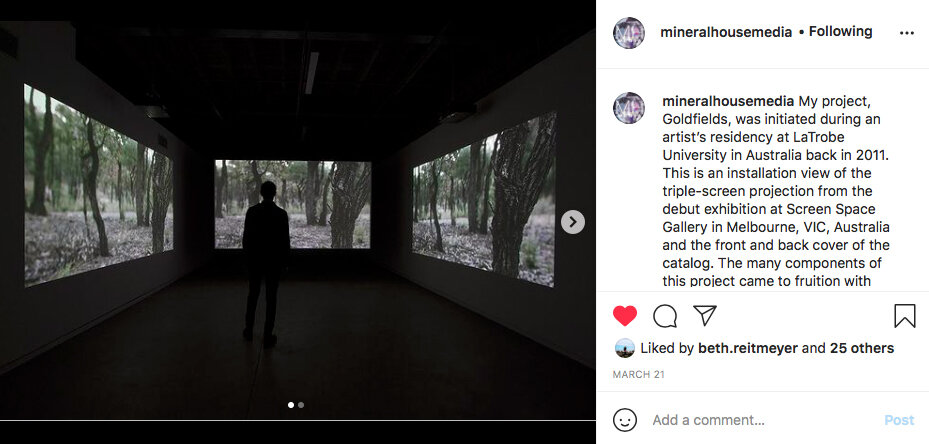

DR: I guess this is mostly to do with the way I work, as that of a responder. Rather than conceiving of a specific plan for projects with particular outcomes in mind, I find that engaging with particular spaces/places directly is quite generative for me. This mode of working came about quite naturally, as I found myself moving from interior, domestic sites to the exterior spaces just beyond. Locations I choose to work in are all similar in that they allow me to think through and visualize the landscape as a very peculiar type of perceptual space, where I consider pictorial conventions and histories of image-making in connection with the presumptions attached to photographic authenticity (often deliberately challenging these things). But the spaces are distinct in that they are all loaded with tons and tons of baggage in terms of what we have done to them, what has occurred within them, and what continues. Most recently, I’ve made projects in the Goldfields region of Australia, in relation to snow- and ice-covered mountains in Iceland and the Canadian Rockies, along the coastal trails used as paths of exile in the Pyrenees Mountains along the Spain/France border, and most recently in the forests of the Pacific Northwest while working with the tree species, Pacific yew.

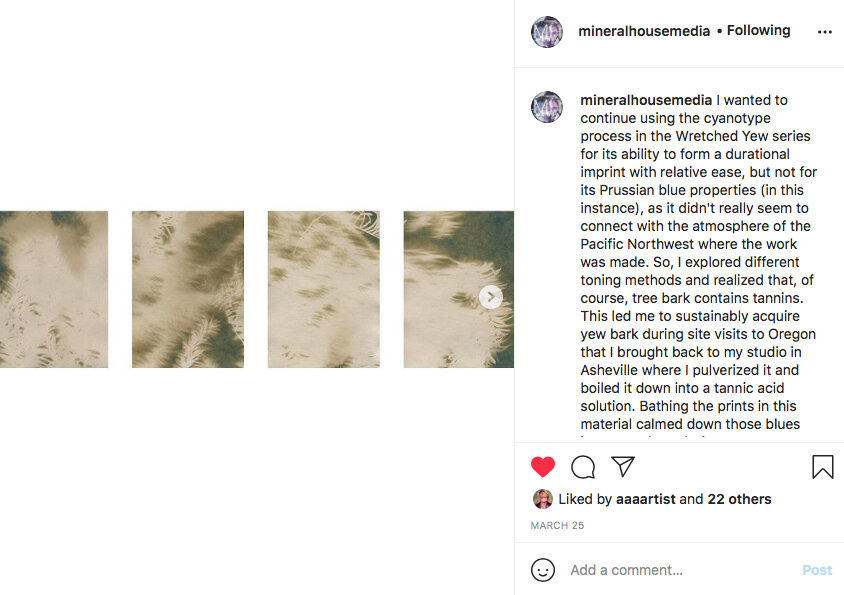

MHM: Can you speak some more on the merit of the cyanotype in comparison to other flat, 2D forms of image-making? I’m thinking specifically about how the cyanotype is a direct and physical imprint of the space you are working in.

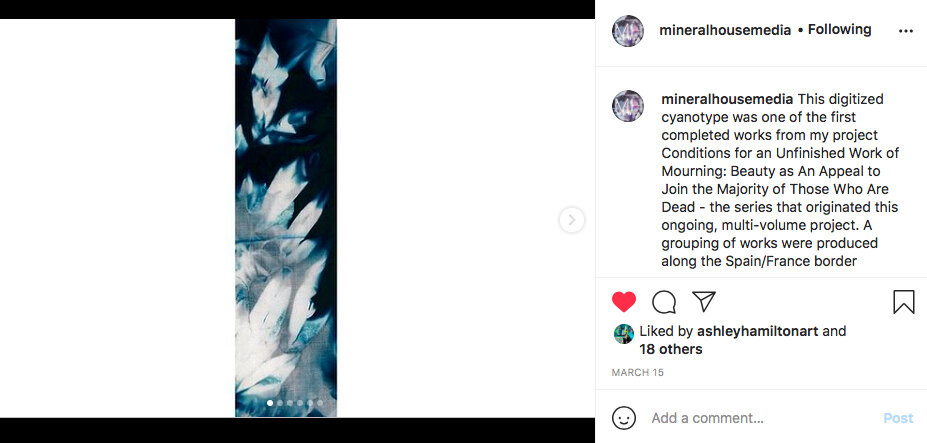

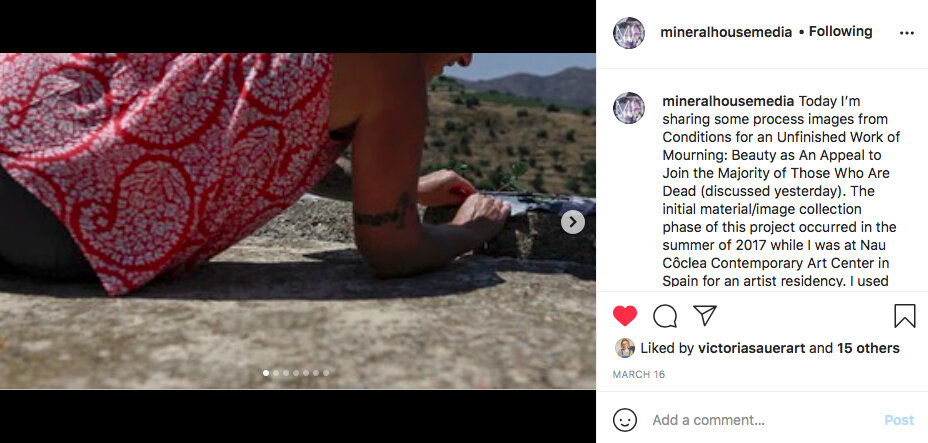

DR: Yes, that’s exactly what drew me to this method - that aspect of the physical imprint. When I set out to start work on that project along the Spain/France border just mentioned, I knew I wanted to incorporate a more direct process. I felt I had exhausted every approach of photo-based representation I could conceive of and was becoming increasingly frustrated with the proliferation of (my own) repeated and expected depictions of landscape, or the world in general. I had been working with multiple and composite images for some time but was starting to veer a bit more toward abstraction in terms of the manner I was breaking things up visually. I realized the resemblance of the space/place wasn’t (always) all that important, but perhaps something could be gained from alluding to - touching on - the referent via camera-less processes, requiring interaction with material and surface. And, because I’m working in a lot of random sorts of spaces with limited access to studio spaces or storage, I found the minimal technical needs of the cyanotype process quite conducive to my mode of working. This method really suited the Spain/France project (Conditions for an Unfinished Work of Mourning: Beauty as an Appeal to Join the Majority of Those Who Are Dead) as exposing those prints by the light of the sun along those mountain paths over durational intervals turned out to be a key aspect of that project. I’ve since continued to use this process, in both similar and different ways.

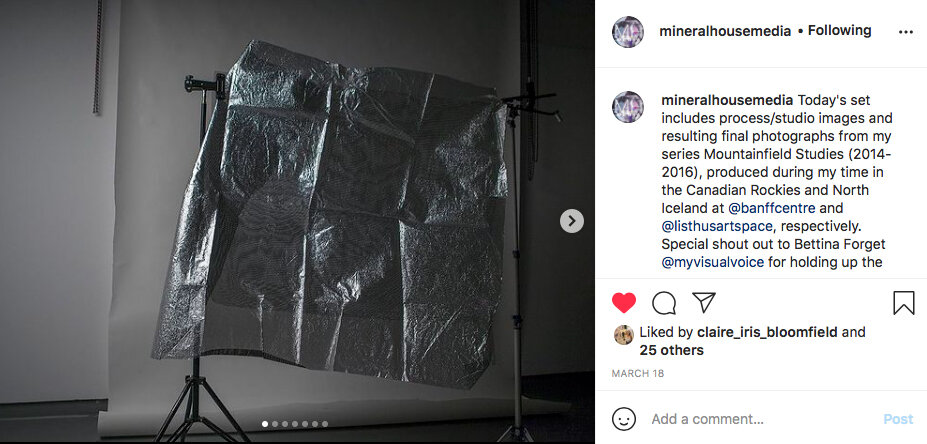

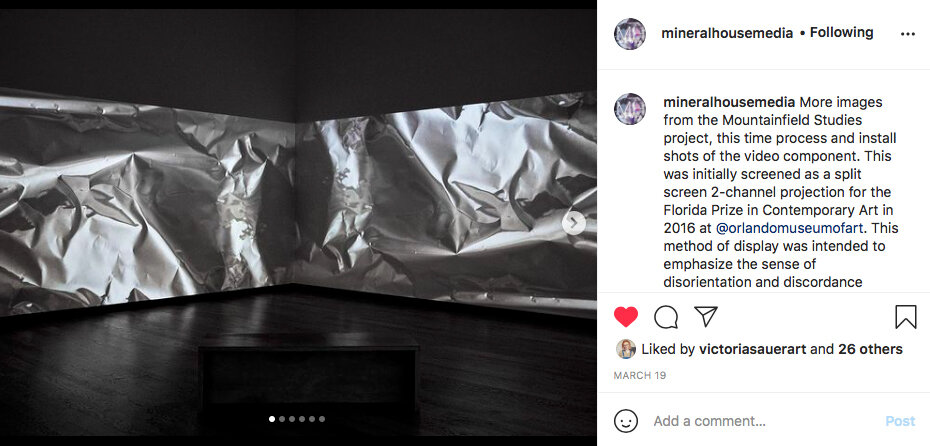

MHM: I notice a lot of cut-and-collage methods of working when representing the disorientating spaces of the Mountainfield Studies. What is more beneficial to you: digital vs physical collaging, or both?

DR: I haven’t done much physical collage and really began that approach to fragmentation within the Mountainfield Studies project somewhat accidentally. It was in the process of thinking through options for multiples (diptychs and triptychs, usually) on the computer monitor, with various groupings of images open at once that I started to notice overlapping/intersecting forms as a possibility. Even though I tend to make a lot of work proofs while in the midst of a project, I don’t always have access to a printer when I’m working away from my studio and have found the digital realm to be quite productive for me in this way.

MHM: Are you currently reading, listening, or watching anything that is inspiring your current practice?

DR: Right now, I’m starting to sift through things in anticipation of getting started on what I believe will be the final volume of the Conditions for an Unfinished Work of Mourning series. This final volume is tentative titled, Descent, and will include engagement with bodies of water in association with this term in varied ways - as passage, downward movement, decline, sinking, legacy, lineage, origination – I plan to seek out locations where relationships to land and water are contested, revered, mourned, misunderstood, or unacknowledged. I landed on this term as most appropriately describing this phase of the project while re-reading an Elizabeth Grosz book, The Nick of Time: Politics, Evolution, and the Untimely, over the summer as I was finalizing the Wretched Yew project. Grosz is a philosopher and feminist theorist, often writing about our relationship to the natural world from a phenomenological, embodied perspective while challenging certain characterizations of Darwinian theories of descent. In relation to this, I’ve got a big stack of other books going including Photography, Trace, and Trauma by Margaret Iverson and Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology, by Astrida Neimanis.

I’ve also been watching the Steve McQueen series of films, Small Axe, which are just incredibly inspiring both in their storytelling and visuality and I just read an article in an old copy of The New Yorker focusing on poet Alice Oswald that had me pretty excited. There is a great quote from Oswald in the article that says, “I think it’s often assumed that the role of poetry is to comfort, but for me, poetry is the great unsettler. It questions the established order of the mind. It is radical […] it works at the roots of thinking.” I just love this.

MHM: Can you elaborate on the importance of collaboration in your works? Whether it’s someone lending vocals, writing, or just another set of hands out in the field of work, how much of it feels your own? When does the work start to feel more about community and the sharing of artistic gifts and wisdom?

DR: Oh, I love that you put it that way - “the sharing of artistic gifts and wisdom.” I hope to get closer to more of that as I continue working, as that really captures the spirit of what I try to get up to out there in the world, with myself and with others - whether they are physically present or not. And this goes back to my earlier comment about being a responder, or respondent. This necessitates interaction, and engagement. There are so many things that wouldn’t have occurred to me, or just simply wouldn’t have occurred without these interactions and engagements that come from collaboration. Though I am a very solitary worker most of the time, these discrete and deliberate contributions from others are incredibly generative, and I really think of all of this as one long, ongoing conversation. So, I’m not sure I can ever say or know what aspects feel entirely my own - I may have a prompt or a starting point for someone else, but we all inform one another. I just love having people thinking and making alongside me, and I hope I offer the right amount of gratitude through various forms of acknowledgment.

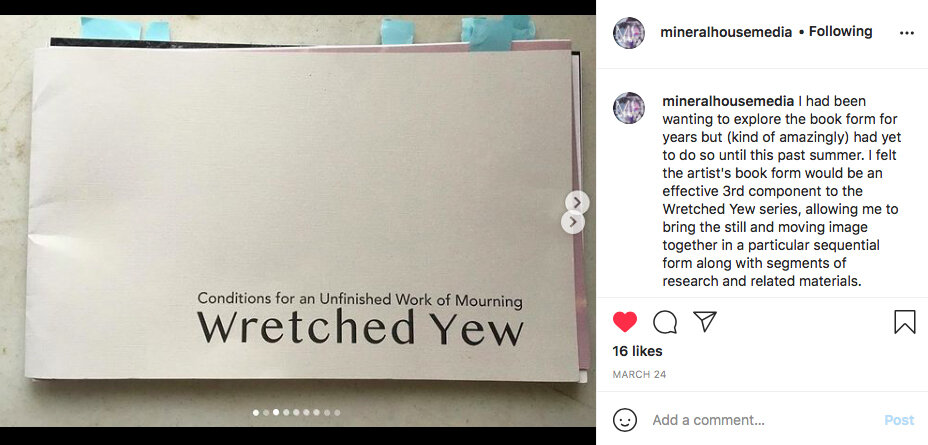

MHM: Do you have future plans to delve into the world of Artist Books beyond your recent Wretched Yew edition? What did the creation of that book offer you that felt new and inspiring?

DR: Absolutely! I still can’t believe it’s taken me this long to actually put things into book form, as I’ve been thinking about it for years, and talking with other artists who work in book form about the possibilities this method offers. In terms of my own approach, I’m less concerned with the book as an object than a temporal container of sorts - another type of moving image, really. Of course, its tangibility is key, allowing the viewer to make their way through the material(s) in time, and to repeat and to return. With this particular book, I was excited to be able to bring together so many elements of the research in terms of text-based excerpts and also archival materials, and to place these alongside finished works and stills from the video. It was kind of like producing an essay film in book form, and I hope to continue this mode for the next component of this project.

Dawn Roe is Professor of Studio Art at Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida. She received her BFA from Marylhurst University in 2002 and her MFA from Illinois State University in 2005. Roe works with still photographs and digital video in both singular and combined forms. Her projects poetically and critically engage with photo-based forms of representation through perceptual studies of culturally charged sites of significance, as well as those presumed to be neutral.

Roe has exhibited widely throughout the U.S. and internationally at venues including The Frost Art Museum, Miami, FL; Filter Photo, Chicago, IL; The White Box/University of Oregon PDX and Newspace Center for Photography, Portland, OR; Screen Space Gallery and Beam Contemporary, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; The Perth Centre for Photography, Perth, WA, Australia; The Cornell Fine Arts Museum, Winter Park, FL; ISU University Galleries, Normal, IL; The Orlando Museum of Art; and Tracey Morgan Gallery, Asheville, NC.

Her work has been featured in many print and on-line journals including Lenscratch, Urbanautica, Floorr, Aint-Bad, The Detroit Center for Contemporary Photography's series Frame/s, Oxford American, and the Routledge print journal, photographies. She has been invited to numerous artist residencies including Nau Côclea Centre for Contemporary Creation, The Banff Centre, Listhús í Fjallabyggðis, The Hambidge Center for the Creative Arts & Sciences, The Visual Arts Centre at LaTrobe University, and the Alden B. Dow Creativity Center. In 2013 she founded the public art space Window (re/production | re/presentation) and served as the curator through 2020, when the project concluded.

Dawn Roe's work is represented by Tracey Morgan Gallery.